The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music: Early music is now mainstream here, thanks in large part to the Madison Bach Musicians, which opened its 10th anniversary season with a first-rate Baroque string program that drew a big and enthusiastic audience, and demonstrated the importance of live performance.

2 Comments

By Jacob Stockinger

Here is a special posting, a review written by frequent guest critic and writer for this blog, John W. Barker. Barker (below) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who hosts an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT FM 89.9. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the Madison Early Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

By John W. Barker

Trevor Stephenson’s Madison Bach Musicians (below, in a photo by John W. Barker) opened their 2013-14 season — which marks the 10th anniversary of the local early music group — with a splendid concert of Baroque string music at the First Unitarian Society’s Atrium Auditorium on Saturday night and then repeated it again on Sunday afternoon at the Madison Christian Community Church on Old Sauk Road.

I went to the Saturday night performance. As always, the proceedings were prefaced by a talk from founder, director and keyboardist Stephenson (below, in a photo by John W. Barker) in his usual witty and informative style.

The rich program proved to be a study in string sounds. Joining harpsichordist Stephenson, along with cellist Anton TenWolde, were five guest players.

Marilyn McDonald (below) is something of the matriarch of Baroque violin playing and teaching, and two of the other players here have been her students: violinist Kangwon Kim and violist Nathan Giglierano. Two others were Brandi Berry and Mary Perkinson, both skilled players known here.

The program was, to a considerable extent a constant switching of these talented violinists. A Concerto for Four Violins without Bass was one of those endlessly fascinating experiments by Georg Philipp Telemann, complete with a finale of fanfares.

Two chamber works by George Frideric Handel (below top) graced separate parts of the program. A Sonata for Violin and Continuo featured the amazingly deft McDonald, with the continuo pair. And a Trio Sonata, Op. 2, No. 9, joined her with the spirited Kim. A Sonata for Two Violins by Jean-Marie Leclair (below, bottom) brought together Berry and Kim.

The first half concluded with a revitalized warhorse: the notorious Canon in D by Johann Pachelbel, reclaimed from all its stupid arrangements, and restored as a contrapuntal delight for three violins with continuo, as well as reunited with its brief concluding Gigue. Perkinson joined McDonald and Berry for this.

Here, I must say, I found another example of how attending a live performance makes all the difference. Watching the players in person, I could follow how leading lines were transferred in turn, canonically, from one violin to another, with a clarity that no recorded performance could allow.

In the second half, after Handel’s Trio Sonata, Stephenson himself played on the harpsichord the final Contrapunctus or fugue from Johann Sebastian Bach’s “The Art of Fugue.” Along the way in this, Bach (below) introduced the motto of his own name, made up of the German musical notes of B, A, C, B-flat (“H” in German notation). And then the piece trails off abruptly where, story has it, Bach dropped his pen forever.

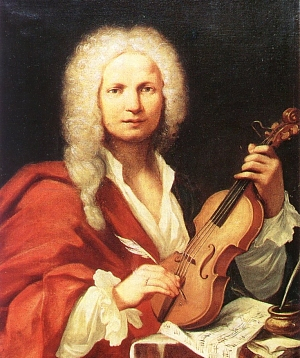

The grand finale was a truly exhilarating performance of the Concerto in A minor for Two Violins, Strings, and Continuo, No. 8 by Antonio Vivaldi (below and in a popular YouTube video with over 3 million hits at the bottom) and included in his Op. 3 publication. (Bach himself so admired this work that he made a keyboard concerto transcription of it.)

Here again, too, I had one of those moments of insight that live performances alone can give.

The players were arrayed, one to a part, with the cello by its harpsichord continuo partner on the far left, the strings then spread out towards the right. The violist Giglierano, in his only appearance, was furthest on the edge.

That isolation from the cello–which really belongs to the continuo, not to the string band–was telling, for it enabled me to appreciate how Vivaldi used the viola as the lowest voice in what is really three-part string writing. This was notably obvious in the middle movement, which was written almost entirely senza basso (without bass). Again, such awareness can come only from a live performance, rather than a recorded one.

It goes without saying that all the performers played with the highest level of skill and stylistic sense, joined with infectious enthusiasm.

MBM concerts used to be held in the lovely intimacy of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church (below top) on Regent Street. Now, they can virtually fill the First Unitarian Society’s Atrium (below bottom), in a photo by Zane Williams) with an audience close to 200 –and a very enthusiastic bunch, at that.

Thirty years ago a concert like this would have been inconceivable. The Madison public was just not as aware and as prepared and as receptive as it has come to be by now. Stephenson and his colleagues in the Madison Bach Musicians are one of the major forces that have brought about that process. How much we owe them!

Tags: American Record Guide, Antonio Vivaldi, Baroque, Cello, Classical music, continuo, Early music, fugue, Georg Philipp Telemann, George Frideric Handel, harpsichord, Jacob Stockinger, Jean-Marie Leclair, Johann Pachelbel, Johann Sebastian Bach, John W. Barker, Madison Bach Musicians, Madison Early Music Festival, Medieval history, Pachelbel Canon in D, Regent Street, Sunday, The Art of Fugue, Trevor Stephenson, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Violin, WORT FM, YouTube

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

Archives

- 2,495,370 hits

Blog Stats

Recent Comments

Tags

#BlogPost #BlogPosting #ChamberMusic #FacebookPost #FacebookPosting #MeadWitterSchoolofMusic #TheEar #UniversityofWisconsin-Madison #YouTubevideo Arts audience Bach Baroque Beethoven blog Cello Chamber music choral music Classical music Compact Disc composer Concert concerto conductor Early music Facebook forward Franz Schubert George Frideric Handel Jacob Stockinger Johannes Brahms Johann Sebastian Bach John DeMain like link Ludwig van Beethoven Madison Madison Opera Madison Symphony Orchestra Mead Witter School of Music Mozart Music New Music New York City NPR opera Orchestra Overture Center performer Pianist Piano post posting program share singer Sonata song soprano String quartet Student symphony tag The Ear United States University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music University of Wisconsin–Madison Viola Violin vocal music Wisconsin Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra wisconsin public radio Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart YouTube