The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music: UW-Madison pianist Christopher Taylor says Bach wouldn’t mind being played on the piano and the public should get to know the less virtuosic side of Liszt. He plays concertos by both composers this weekend with the Madison Symphony Orchestra.

4 Comments

By Jacob Stockinger

Today’s guest Q&A is the acclaimed UW-Madison pianist Christopher Taylor (below), who won a bronze medal in the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition and who has been praised by critics around the world.

Taylor will play a big role this weekend in what, for The Ear, is the most interesting program of the season from the Madison Symphony Orchestra (below).

The program, to be performed under the baton of longtime MSO music director John DeMain, includes the Piano Concerto No. 4 by Johann Sebastian Bach and the Piano Concerto No. 1 by Franz Liszt. The soloist for both is the dynamic and versatile Taylor (below), the resident virtuoso at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music.

The second half of the program is the Symphony No. 7 by the Late Romantic Austrian composer Anton Bruckner – the first time the MSO has tackled one of Bruckner’s mammoth symphonies.

Performances are in Overture Hall in the Overture Center. Times are Friday at 7:30 p.m.; Saturday at 8 p.m.; and Sunday at 2:30 p.m.

Tickets are $12-$84.

For details, go to https://www.madisonsymphony.org or call the Overture Center Box Office at (608) 258-4141.

Taylor recently agreed to an email Q&A with The Ear:

What do you say to early music and period instrument advocates about performing Bach on a modern keyboard versus a harpsichord? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each?

In matters musical I hope to foster a generally tolerant attitude. I think our art form is a broad and diverse enough domain to allow for the peaceful coexistence of interpretations that pursue varied goals.

Some may seek to recreate, in as precise a way as possible, the experiences of listeners living back in Bach’s day, a perspective that can undoubtedly prove illuminating and satisfying for contemporary audiences.

Others may pursue interpretations that employ more recent, or even completely novel, musical resources, with results that Bach himself might well find startling were he suddenly to return.

Still, given Bach’s documented flexibility regarding instrumentation — the Keyboard Concerto No. 4 was probably originally composed for oboe — I like to think he would be open-minded both towards the piano’s sonority and the interpretive possibilities it suggests.

The piano’s rich and varied sound undoubtedly fits naturally into the modern concert hall setting, and for me personally its character is what I understand and appreciate best. But again, I am always eager to learn about alternative approaches, and hope that others will listen to me with a similar mindset. (Below, Taylor is seen with the unusual two-keyboard Steinway piano he uses to play Bach’s “Goldberg” Variations.)

How would you compare the Keyboard Concerto No. 4 to Bach’s other ones?

Like all the Bach concertos this work possesses irresistible energy and momentum, paired with lyricism and ingenious construction. It strikes me as a particularly cheerful specimen — not so imposing or stern as the D minor or F minor concertos, for instance, but more modest in scale and upbeat in mood.

Right from the opening the first movement features an interesting back-and-forth relationship between the soloist and orchestra, with the keyboard seeming suitably soloistic on some occasions, more accompanimental at other moments, and completely united with the strings yet elsewhere.

The slow middle movement has particularly long phrases and sinuous lines, while the finale displays remarkable rhythmic variety, with relatively staid eighth notes taking turns with bustling sixteenth-notes and downright scrambling thirty-second-notes. (You can hear the Bach concerto for yourself in the YouTube video below that features the British pianist Nick Van Bloss who, curiously, suffers from Tourette’s Syndrome except when he is playing.)

A lot of listeners know you especially for your interpretations of modern and contemporary composers such as William Bolcom, Gyorgy Ligeti, Derek Bermel and especially Olivier Messiaen. But you are also known for your performances of the “Goldberg” Variations. What are the attractions of Bach’s music for you?

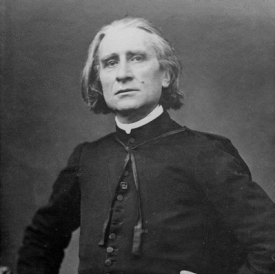

I find in Bach (below) the supreme balance of heart and brain. It is music whose intricacy provides endless material for intellectual stimulation and study, but which nonetheless, in its restrained and elegant way, evokes every imaginable shade of human feeling.

It is hardly surprising that composers as diverse as Ludwig van Beethoven, Frederic Chopin and Arnold Schoenberg found inspiration in his immortal creations.

Playing his music is a foundational skill for me, providing essential training and background when I approach, for instance, the more recent composers whose challenging works you mention.

Liszt is known as probably the greatest piano virtuoso in history who reinvented keyboard technique. How do you see the first concerto in terms of both deeper musicality and sheer spectacle and technical virtuosity?

While Bach may sometimes be stereotyped as hyper-academic and dry, the stereotype associated with Liszt is quite the opposite: flashy and intellectually shallow.

Neither caricature captures the reality, and I hope that this week’s pair of concertos helps to illustrate the unexpected facets and depths of both composers.

While I have been familiar with the Liszt from a very early age, I only performed it for the first time fairly recently. While learning it I found myself continually surprised by its formal sophistication and intriguing quirkiness.

Certainly it has its moments of raw virtuoso display, but these only constitute one ingredient in a varied dramatic structure. Just as important are the lyrical characters (sometimes cut off short), the playful elements, the eccentric, the grand, the angelic. I have thus come to appreciate how experimental, individualistic, and sophisticated this work really is.

How do you view Liszt as a composer compared to his reputation as a performer and teacher? What should the public pay attention to in the Liszt Concerto and is there anything special or usual you try to do with the score?

As I suggested above, I think there’s often a tendency to underestimate Liszt’s compositional import — although admittedly he did produce certain works that feed into the stereotypes distressingly well.

I will hope to bring out this concerto’s interplay of characters and its individualism as vividly as possible. The virtuoso elements will play their part, but I do not wish for them to be the sole focus. (You can hear the concerto played by Martha Argerich in the YouTube video that is below.)

Tags: "Goldberg" Variations, Arnold Schoenberg, Arts, Bach, Baroque, Britain, Chopin, Classical music, concerto, Derek Bermel, English, Franz Liszt, György Ligeti, Jacob Stockinger, Johann Sebastian Bach, John DeMain, Late Romantic, Liszt, Ludwig van Beethoven, Madison, Madison Symphony Orchestra, Martha Argerich, Music, Nick Van Bloss, Oboe, Olivier Messiaen, Orchestra, Piano, Piano concerto, Romanticism, Steinway, symphony, Tourette's, UK, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music, University of Wisconsin–Madison, WILLIAM BOLCOM, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, YouTube

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

Archives

- 2,493,305 hits

Blog Stats

Recent Comments

| welltemperedear on What do you think of the… | |

| Scott on What do you think of the… | |

| welltemperedear on Yunchan Lim’s Chopin etudes ar… | |

| bratschespeilerin on What do you think of the… | |

| MARVIN P WICKENS on Yunchan Lim’s Chopin etudes ar… |

Tags

#BlogPost #BlogPosting #ChamberMusic #FacebookPost #FacebookPosting #MeadWitterSchoolofMusic #TheEar #UniversityofWisconsin-Madison #YouTubevideo Arts audience Bach Baroque Beethoven blog Cello Chamber music choral music Classical music Compact Disc composer Concert concerto conductor Early music Facebook forward Franz Schubert George Frideric Handel Jacob Stockinger Johannes Brahms Johann Sebastian Bach John DeMain like link Ludwig van Beethoven Madison Madison Opera Madison Symphony Orchestra Mead Witter School of Music Mozart Music New Music New York City NPR opera Orchestra Overture Center performer Pianist Piano post posting program share singer Sonata song soprano String quartet Student symphony tag The Ear United States University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music University of Wisconsin–Madison Viola Violin vocal music Wisconsin Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra wisconsin public radio Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart YouTube