The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music: The Madison Bach Musicians perform Baroque and Renaissance English music this coming Friday night and Sunday afternoon

Leave a Comment

ALERT: The strike by the players in the Philadelphia Orchestra has been settled. For details, go to this website:

For more background about that strike and others, which The Ear writes about yesterday, go to:

By Jacob Stockinger

The Madison Bach Musicians will open its 2016-17 season this coming weekend with two performances of a program that features English music from the Baroque and Renaissance eras.

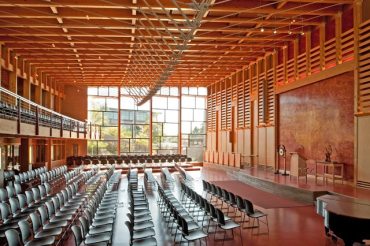

The first performance is this Friday, Oct. 7, at 7:30 p.m., preceded by 6:45 lecture, in the Atrium Auditorium (below, in a photo by Zane Williams) of the First Unitarian Society of Madison, 900 University Bay Drive.

The second is this coming Sunday, Oct. 9, at 3:30 p.m., preceded by a 2:45 lecture, at the Holy Wisdom Monastery (below), 4200 County Highway M in Middleton.

If bought in advance, tickets are $28 for the general public and $23 for students and seniors over 65; at the door tickets will be $30 and $25, respectively. Student rush tickets are $10, require a student ID and are available 30 minutes before the lectures. For more information, visit www.madisonbachmusicians.org

The program features: Sonata in Four Parts in F major “Golden Sonata” by Henry Purcell (1659−1695); Suite No. 2 in D major from “Consort of Four Parts” by Matthew Locke (c. 1621−1677); Songs to texts by William Shakespeare by Robert Johnson (1583−1633); “Diverse bizzarie Spra La Vecchia” by Nicola Matteis (c. 1650−c. 1709); Division No. 7 for two bass viols by Christopher Simpson (c. 1606−1669); “Solus cum sola” for solo lute solo by John Dowland (1563−1626); “The Broken Consort” Part 1, Suite no. 2 in G major by Matthew Locke; “The Carman’s Whistle” by William Byrd (c. 1540−1623); “Light of Love” by Anonymous as arranged by David Douglass; “John Come Kiss Me Now” by John Playford (1623−c. 1686) as arranged by David Douglass; “Long Cold Night” and “Queen’s Jig.”

Performers include: Dann Coakwell, tenor; David Walker, lute and theorbo; Kangwon Kim violin and concertmaster; Brandi Berry, violin; Anna Steinhoff and Martha Vallon, viola de gamba; and Trevor Stephenson, harpsichord.

Here are some edited notes by MBM founder and director Trevor Stephenson (below):

Madison Bach Musicians is delighted to start off its 13th season with a foray into new repertoire for the group: English music from the Renaissance and Baroque.

A special feature of the program will be the recognition in song of the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare (1564-1616).

Both the smaller lute and the larger theorbo were considered ideal for accompanying the voice in songs, and the theorbo could project a bit better in larger ensembles.

Like the lute, the viola da gamba is also fretted, but it is bowed and not plucked. Moreover, the gamba is held between the legs, the “gams,” and its name literally means “viol of the legs.”

The baroque violins we’ll use in this program will be strung in the usual fashion of the 16th and 17th centuries, that is, with gut strings (from dried sheep intestine); and the bows will be of the Elizabethan “short” variety (shorter length, and with the stick arching away from the hair), which make them ideally suited for the intricate articulations and lively dance rhythms of this repertoire.

All of these instruments enjoyed great popularity in England during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Henry Purcell (below) flourished during the arts boom of the Restoration period under King Charles II and is widely known for his theater music and operas. However, he also wrote quite a bit of instrumental music.

The four parts of this sonata refers here not to numbers of movements, but to the number of simultaneous instrumental lines—in this case, four, which is notably different from the typical three-part (or trio sonata) Italianate texture of the 17th century.

The Purcell sonata is followed by an instrumental Suite in D major by Matthew Locke (c. 1621-1677). Locke was a close friend of the Purcell family and in particular of Purcell’s father, Henry Purcell Sr. The younger Henry Purcell wrote a musical elegy on Locke’s death in 1677.

Locke’s years of greatest musical activity in London began as the period of Puritanical Commonwealth rule, under Oliver Cromwell, was waning in the late 1650’s. The Commonwealth had severely restricted the theater and the arts in general. Fun fact: Locke (below) was the first composer to indicate a musical crescendo and decrescendo in a score.

The texts for the songs are from various Elizabethan poets—John Fletcher, John Webster and Shakespeare himself—and all of the music was composed by lutenist Robert Johnson (below, 1583-1633).

Johnson worked closely with Shakespeare in theatrical productions at the court of James I during the first few years of the 17th century. Johnson even provided music for Shakespeare’s original production of “The Tempest.”

The first part of the MBM program will conclude with two works that explore a favorite 17th-century technique of ornamentation over a repeated bass line, sometimes called a ground bass or chaconne.

The first is by the Italian virtuoso violinist Nicola Matteis (below, in a painting by Gottfried Kneller, c. 1650-1709), who enjoyed a successful career in London during an era when the English were importing Italian music masters by the dozens.

The second work, by Christopher Simpson (below, c. 1606-1669), explores “divisions” or variations tossed back and forth between two bass viols (gambas) while they simultaneously repeat a ground bass.

The second half of the program will feature songs for tenor and voice by John Dowland (below). We’ll also play Locke’s Broken Consort, “broken” meaning “mixed”–in that violins and gambas, which were considered in Elizabethan times to be artistically quite different instruments—were being asked by the composer to play nicely together.

Following that, I’ll play a rousing set of variations for harpsichord, “The Carman’s Whistle,” by William Byrd (below).

And to conclude the program, the consort will play a set of sprightly dances originally published in 1651 in the collection “The English Dancing Master” by John Playford (below).

Tags: Arts, Baroque, bow, chaconne, Christopher Simpson, Classical music, dance, David Douglass, Early music, Elizabethan, Elizabethan England, Elizabethan music, English, English Renaissance, ground bass, hair, harpsichord, Historically informed performance, Italian music, Italy, Jacob Stockinger, John Playford, King Charles II, lecture, London, lute, Madison, Madison Bach Musicians, Matthew Locke, Music, Nicola Matteis, Orchestra, period instruments, Purcell, Renaissance, restoration, Robert Johnson, score, Shakespeare, Sonata, song, Student, Suite, tenor, theorbo, trio, United States, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Viola, viola da gamba, Violin, vocal music, William Byrd, William Shakespeare, Wisconsin

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

Archives

- 2,491,540 hits

Blog Stats

Recent Comments

| Brian Jefferies on Classical music: A major reass… | |

| welltemperedear on What made Beethoven sick and… | |

| rlhess5d5b7e5dff on What made Beethoven sick and… | |

| welltemperedear on Beethoven’s Ninth turns 200… | |

| Robert Graebner on Beethoven’s Ninth turns 200… |

Tags

#BlogPost #BlogPosting #ChamberMusic #FacebookPost #FacebookPosting #MeadWitterSchoolofMusic #TheEar #UniversityofWisconsin-Madison #YouTubevideo Arts audience Bach Baroque Beethoven blog Cello Chamber music choral music Classical music Compact Disc composer Concert concerto conductor Early music Facebook forward Franz Schubert George Frideric Handel Jacob Stockinger Johannes Brahms Johann Sebastian Bach John DeMain like link Ludwig van Beethoven Madison Madison Opera Madison Symphony Orchestra Mead Witter School of Music Mozart Music New Music New York City NPR opera Orchestra Overture Center performer Pianist Piano post posting program share singer Sonata song soprano String quartet Student symphony tag The Ear United States University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music University of Wisconsin–Madison Viola Violin vocal music Wisconsin Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra wisconsin public radio Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart YouTube