The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music: The Festival Choir of Madison gives a lovely and lovingly committed exploration of the rarely heard setting of the Russian Orthodox All-Night Vigil by Tchaikovsky.

1 Comment

By Jacob Stockinger

Here is a special posting, a review written by frequent guest critic and writer for this blog, John W. Barker. Barker (below) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who for 20 years hosted an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT 89.9 FM. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the Madison Early Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

By John W. Barker

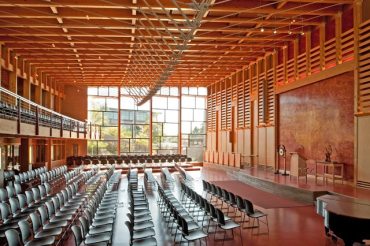

The Festival Choir of Madison (below top, in a photo by Stephanie Williams) undertook a brave venture into difficult novelty last Saturday night in the Atrium Auditorium (below bottom in a photo by Zane Williams) at the First Unitarian Society of Madison.

The venture involved the setting of the All-Night Vigil ritual for a cappella choir by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky .

One does not instantly think of Tchaikovsky as a choral composer, or in particular as a composer of sacred music. But he greatly admired the traditions of Russian Orthodox liturgical music, as it had been redefined in the 18th and 19th centuries, as bound up in the very special Russian propensity for powerful choral singing.

In 1879 he made a setting the text of the basic Orthodox Eucharistic service, the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, published as his Op. 41. It was not well received, but Tchaikovsky (below) went on in 1882 to set the cycle of Vespers and Vigil texts, his Op. 52. Indeed, during the 1880s, he composed a dozen other settings of Orthodox liturgical texts.

By his time, the functioning choral music of the Russian Orthodox Church, used amid traditional chants, was generally written by composers who specialized in the genre, quite separate from the growing school of Russian secular composers.

There were some jealousy and resentment expressed by the former against the latter. Few Russian musicians managed personally to bridge the gap between the sacred and the secular. Alexander Gretchaninoff (below) was one of the few who were successful in both.

Tchaikovsky was not given much credit for his religious writing, and his liturgical works are generally ignored. It was his successor, as it were, Sergei Rachmaninoff (below), who achieved true musical greatness in leaping from secular composition into sacred, with his own settings of the Chrysostom Liturgy and the All-Night Vigil. Indeed, the latter has come by now to be recognized as a masterpiece and is ever more frequently performed internationally. (You can hear a section in a YouTube video at the bottom.)

The Festival Choir’s conductor, Bryson Mortensen (below, with singer Nancy Vedder-Shults in a photo by Jon Lanctot) chose to preface the performance of the Tchaikovsky score with one movement from the Rachmaninoff counterpart. It was a good idea, though the brief section chosen, gorgeous in itself, was not enough to point up the contrasts in the two composers’ approaches.

Rachmaninoff’s setting is charged with imagination and rich elaboration of the traditional; chants that are the music’s foundations. He even included parts for solo voices, which Tchaikovsky did not.

On the contrary, Tchaikovsky’s approach is really quite conservative and even simplistic. He chose to devise harmonizations of the chants and their liturgical formulas, in accomplished but texturally unadventurous realizations, relying upon the sonorous Russian choral sound to carry the effects. The results are quite lovely, if a bit repetitive as a cycle.

Mortensen made one interesting attempt to bring some variety into the proceedings by having three spiritual poems by Russian writers interspersed with the music at three points. An interesting idea, but the poems chosen were rather bland, and were not well delivered.

It is more a question is the musical performance. Setting Western choirs to singing Church Slavonic texts not part of their culture is not always easy. The singers clearly were working earnestly at it.

But Church Slavonic (like modern Russian) is rich in consonants, and these were just not spat out with the spirit they required. In addition, it seems that only Russian choirs have the gutsy basses that can provide the rock-solid foundation needed for the overall texture. The Festival Singers just could not muster up such power.

Or perhaps, as I suspect, maestro Mortensen (below) chose to restrain them in the interests of a beautifully balanced and blended choral sound — which he certainly achieved — rather than to risk having a section run away with the show. On the other hand, it seemed to me that by the final sections of the score he was infusing a really exciting range of dynamic inflection into the performance.

All in all, one had to admire what this conductor and choir achieved. How often, anywhere, is one likely to encounter this music in live performance? In this concert we were given a chance, and one in which the challenges were met with devotion and lovely music-making. Slava!

Tags: a cappella, Alexander Gretchaninoff, All-Night Vigil, American Record Guide, Arts, Bryson Mortensen, Choir, choral music, Classical music, Festival Choir of Madison, First Unitarian Society of Madison, Jacob Stockinger, John W. Barker, Madison, Music, Rachmaninoff, Rachmaninov, Russian Orthodox Church, Singing, Tchaikovsky, WORT, WORT-FM 89.9, YouTube

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

Archives

- 2,491,655 hits

Blog Stats

Recent Comments

| MARTIN LUTHER LUTE |… on Classical music: Who was the e… | |

| Brian Jefferies on Classical music: A major reass… | |

| welltemperedear on What made Beethoven sick and… | |

| rlhess5d5b7e5dff on What made Beethoven sick and… | |

| welltemperedear on Beethoven’s Ninth turns 200… |

Tags

#BlogPost #BlogPosting #ChamberMusic #FacebookPost #FacebookPosting #MeadWitterSchoolofMusic #TheEar #UniversityofWisconsin-Madison #YouTubevideo Arts audience Bach Baroque Beethoven blog Cello Chamber music choral music Classical music Compact Disc composer Concert concerto conductor Early music Facebook forward Franz Schubert George Frideric Handel Jacob Stockinger Johannes Brahms Johann Sebastian Bach John DeMain like link Ludwig van Beethoven Madison Madison Opera Madison Symphony Orchestra Mead Witter School of Music Mozart Music New Music New York City NPR opera Orchestra Overture Center performer Pianist Piano post posting program share singer Sonata song soprano String quartet Student symphony tag The Ear United States University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music University of Wisconsin–Madison Viola Violin vocal music Wisconsin Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra wisconsin public radio Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart YouTube