The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music Q&A: Meet opera director David Ronis who makes his local debut in the University Opera’s production of Benjamin Britten’s “Albert Herring” this Friday night in Music Hall with additional performances on Sunday afternoon and Tuesday night.

4 Comments

By Jacob Stockinger

You may recall that the longtime director of University Opera William Farlow retired last spring. While no permanent successor has been named yet, the impressively qualified David Ronis, from the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College, City University of New York (CUNY), was chosen from a national search and is serving as a guest director this academic year.

Ronis (below, seen talking to the cast on stage) makes his University of Wisconsin-Madison debut this Friday night at 7:30 p.m. in Music Hall, at the foot of Bascom Hill, with a production of British composer Benjamin Britten’s comic opera “Albert Herring.” (The opening scene from a Los Angeles Opera production can be heard at the bottom in a YouTube video.) Additional performances are on Sunday afternoon at 3 p.m. and Tuesday night at 7:30 p.m.

Tickets are $22 general admission; $18 for senior; and $10 for student. They are available at the door and from the Wisconsin Union Theater Box Office or call (608) 265-ARTS (2787)/ Buy in person and you will save the service fees.

Here are links with more information about the opera and about Ronis, including a fine profile interview done by Kathy Esposito, the public relations and concert manager at the UW-Madison School of Music:

http://www.music.wisc.edu/2014/09/19/david-ronis-theatrical-emphasis/

http://www.music.wisc.edu/faculty/david-ronis/

http://www.music.wisc.edu/2014/09/19/university-opera-presents-brittens-albert-herring/

And here is a link to David Ronis’ personal website:

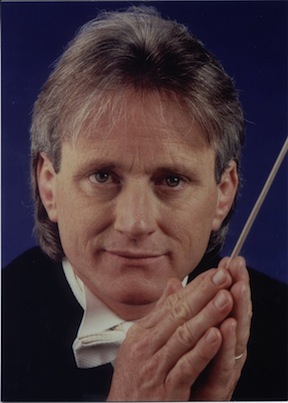

Finally, here is the email Q&A that David Ronis (below, in a photo by Luke Delalio) gave to The Ear:

Can you give readers a brief introduction to yourself, including when and how you started learning music, your early training and formative experiences, your major professional accomplishments and some personal information like hobbies and other interests as well as current and future plans for your career?

I grew up on Long Island, did my undergraduate degree (a B.F.A. in Voice) at Purchase College, and have lived in Manhattan ever since. I studied both piano and voice as a kid and, in high school, was very much involved in musical theater. After graduating from Purchase, I supported myself by doing a lot of professional choral singing.

Soon after, I started getting hired to sing character tenor roles in opera companies in U.S, Europe and Asia, which I did for a number of years. One of the highlights was being a part of Leonard Bernstein’s A Quiet Place/Trouble in Tahiti when it was done at La Scala Milan, the Kennedy Center and the Vienna State Opera.

At one point in the mid-’90s, when I had less than a full year of regional opera work, I started auditioning for Equity musical theater jobs and was cast in the Los Angeles company of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast.

In opera circles, I was considered to be a “good actor.” But, to forgive myself (and others), I didn’t really know from good acting! In LA, my new colleagues and friends were actors, as opposed to singers and musicians, and I started seriously questioning my own (lack of) acting technique. After three years of doing Beauty –- in both LA and on the national tour -– I went back to New York, got into in a heavy-duty acting class, and started working in spoken theater, TV commercials (I have some very funny stories about that), and independent films, as well as continuing to sing in opera regionally.

My work in theater completely changed my perspective on stage work in opera and I found myself newly critical of much of the operatic acting I saw.

One day, my friend Paul Rowe (below) –- who teaches voice at the UW-Madison — was in New York hanging out at my apartment (this is very vivid in my mind) and he said something like, “David, you should put this together. You’re now an accomplished actor as well as a singer and you have a pretty unique perspective on how one affects the other.” Bingo!

Long story short: I started teaching Acting for Singers classes, doing small directing projects, and very soon got hired at Queens College to direct the Opera Studio. Almost immediately, this transition from performing to teaching just felt right.

I was hired as an Adjunct Lecturer at Queens with only a bachelor’s degree, and decided that I should probably have at least a master’s. So I enrolled in a terrific M.A. L.S. (Master of Arts in Liberal Studies) program at a de-centralized SUNY school, Empire State College. The M.A.L.S. was probably one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. It is a self-designed, inter-disciplinary research degree in which the candidates have to articulate their areas of academic inquiry and pursue them by creating individual courses and working with tutors. Over 2 ½ years, I wrote about 300 pages of material focused on operatic acting and production, research that I still regularly call upon in my teaching.

What are my principal influences? I’d say that my principal acting teacher, Caymichael Patten, is a big one. Cay’s a terrific, tough teacher who tells it like she sees it. She has an uncanny knack for “being inside your head –with you.” I learned a huge amount from her and, in many ways, have modeled my teaching on Cay’s. I also have a number of friends – all opera directors working in academia as well as professionally, who are on the same page as I am as far as operatic acting training. They’ve been big influences too -– Stephen Wadsworth (below, who teaches at the Juilliard School) and Robin Guarino, to name just a couple.

As for the future, who knows? I’ve actually never been one to have a detailed life plan. I’ve been very fortunate that opportunities have come my way and I’ve just followed my nose. I do know one thing -– that my passion for directing and teaching seems to be growing (if that’s even possible) and that I very much enjoy working in a university environment.

As an East Coast native, how do you like the Midwest, Madison and the especially the UW-Madison?

I’ve spent plenty of time in the Midwest, mostly working. So I “get” the Midwest and I’m comfortable here. I’m finding what “they say” about Madison to be true -– that it’s a pretty unique place within the Midwest — culturally, politically, intellectually.

I think these are things that make people who are kind of East Coast-centric, like myself, feel more at home, when “home” means lots of intellectual and artistic stimulation. What’s not to like about a city where everyone reads the New York Times and The New Yorker magazine and goes to the Madison Symphony Orchestra!

Why did you choose “Albert Herring” by Benjamin Britten (below top) to do this semester and “The Magic Flute” by Mozart (below bottom) to do second semester? Have you staged them before? What would you like audience members here to know about your productions of them?

I make repertoire decisions based on a variety of factors. This year, we needed to do a piece with small orchestral forces in the fall and a full orchestra show in the spring.

I also like to do shows that involve a good number of students. Both the Britten and the Mozart fit those descriptions.

Also, the “who do we have at school” factor is big. We need to do operas that we can cast well from the student population.

And, most importantly, I consider the educational value of various shows. Albert Herring is not only a great piece of music and theater, but there’s so much that the students learn from working on it. The roles are difficult, both vocally and musically. And since it’s a big ensemble show, students are challenged to develop their ensemble singing and acting skills. So far, I’m very pleased with the results.

I’ve directed The Magic Flute before. We’re going to do a version of a production I did some years ago that locates the drama vaguely in a South Asian environment. Flute, for all of its brilliance, is kind of a dramaturgical mess. Who are the truly good and bad guys/gals? Where do we start and where do we end up and what do each of the characters learn for having gone on the journey?

My take on the story very indirectly alludes to a conflict between East (Sarastro) and West (Queen of the Night), and attempts to examine the two opposing forces on the most basic, human level – even if they are iconic figures. Why makes the Queen tick? Why did Sarastro “steal” her daughter and why is he “holding her captive?” These are the questions that intrigue me.

Was there an Aha! Moment – a work or performer, a concert or recording – that made you realize that you wanted to have a professional life in music and specifically in opera?

My Aha! moment? OK, you’re going to think I’m a nerd. As a high school senior, I took a philosophy elective in which I was reading people like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. At the time, I was obsessed with an LP called “The Genius of Puccini” -– essentially excerpts from operas by Puccini (below) –- which I would play over and over again in my room. I recall going into my parents’ room one night, with record blaring in the background, and ranting on about what I was reading and how it described exactly what filled me up like nothing else. (Cue the big ensemble from the first act of Turandot). From that moment, it was all downhill!

Is there anything else you would like to add or say?

I’d just like to encourage people to come to both University Opera productions. We’ve got a terrific cast for Albert Herring, not to mention an incredibly talented and articulate young conductor in Kyle Knox (below)– Kyle is truly someone to keep your eye on.

We’ve been having so much fun during rehearsals – laughing a lot! I firmly believe that spirit transfers across the proverbial footlights.

If any of your readers are hesitant (perhaps because they tend to respond to 19th century Romantic pieces and might be reticent to go to an opera with which they’re not familiar), I can confidently say that Albert Herring is a very accessible piece –– extremely entertaining and, at times, quite moving. The physical production is coming along –- all in all, I’m very excited about the show.

Tags: Aaron Copland School of Music, acting, Albert Herring, Arts, Beauty and the Beast, Benjamin Britten, City University of New York, Classical music, Conducting, David Ronis, director, drama, Empire State College, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacob Stockinger, Juilliard School, Leonard Bernstein, Los Angeles, Los Angeles Opera, Madison, Madison Symphony Orchestra, Mozart, New York City, opera, Orchestra, Puccini, Schopenhauer, Singing, stage director, Turandot, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Vienna State Opera, vocal music, Walt Disney, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, YouTube

Classical music: Why am I turning off Wisconsin Public Radio more often? Too many second-rate composers and works? Too much harp music? Too many ads and promos? What do you think? Plus, UW baritone Paul Rowe sings Baroque cantatas this Sunday afternoon.

21 Comments

REMINDER: In a FREE concert this Sunday at 2 p.m. in Mills Hall, University of Wisconsin-Madison baritone Paul Rowe (below) will perform a promising and appealing concert of cantatas for solo voice and instruments composed between 1600 and 1720. Performers include John Chappell Stowe, harpsichordist and organist; Eric Miller, cellist and viola da gambist; and Alice Bartsch and Madlen Horsch Breckbill, violinists.

The program includes: Small Sacred Concertos by: Ludovico da Viadana (1564-1645) “Salve, Regina” and “Cantemus Domino” from Cento concerti ecclesiastici (1602); Heinrich Schutz (1585-1672), “Ich liege und schlafe,” SWV 310 from “Kleine Geistliche Konzerte,” Op.9 (1639); Secular Cantatas by: Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764): “Thetis” (1718); George Frideric Handel (1685-1759): “Cuopre tal volta il cielo” (circa 1708); and J. S. Bach (1685-1750): “Amore traditore,: BWV 203 (circa 1720).

By Jacob Stockinger

It’s a Friday morning as I am writing this.

And I just turned off “Morning Classics” on Wisconsin Public Radio.

Again.

That saddens and disappoints me because I have long loved and listened to WPR, and I almost always write as a close friend rather than a critic. The WPR people I know and have met, from director Mike Crane to many of the show hosts, are all fine, intelligent and sensitive people.

But lately I find myself turning off Wisconsin Public Radio more than I ever have before.

Why is that? I began to wonder.

Some of it has to do with recent schedule changes.

Today is Friday and since a few weeks ago that means the 9-11 a.m. Morning Classics slot will feature the weekly Classics By Request show.

Alas!

Requests used to be on Saturday morning. That was a great slot in which smaller excerpts of usually well-known works set up the longer, often lesser well-known opera broadcasts. It also allowed children and students to listen to snippets of tried-and-true masterpieces.

True, the morning show’s new host Ruthanne Bessman (below) still seeks out requests from kids. But does anyone want to bet that most of the children are in school when the requests get played on Friday from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m.?

Sorry, like some other good and loyal WPR friends I know, I turn it off.

Then too I find that WPR is programming too much harp music these days, mostly in the morning but not exclusively. I mean, I like the harp probably as much as anyone — excepting harp players of course. But I the harp in its place, which is usually as an ensemble instrument with an orchestra or smaller chamber group, where it can add a distinctive texture and tone.

But I am hearing too many solo works for harp and too many goofy and thoroughy forgettable harp pieces, especially arrangements. One recent offering was J.S. Bach’s keyboard “Italian Concerto” arranged for Harp Ensemble. That is misusing such a fine member of the family of “brunch instruments.” Kind of like an arrangement I recently heard of Tomaso Albinoni’s famous Adagio for Strings and Organ that used the flute, played by the famous James Galway, to suck all the pathos out of the piece.

It turned the profound into the pleasant.

So once again I turned the radio off.

Maybe audience surveys and focus groups tell WPR executives that the public likes the harp and other members of the “brunch instrument” family that much. But I don’t. Do you?

It all makes me miss the former morning host Anders Yocom (below top), who used to play what he called “The Minimum Daily Requirement” of Bach (below bottom) every morning. And who else but Bach – serious Bach – can meet that daily requirement? Yocom also usually featured big and beefy concertos and symphonies and sublime chamber music .

I mean the kind of music I want to hear mostly is the kind of music you don’t want to live without.

It is the kind of music that led the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche to proclaim” “Life without music would be a mistake.”

WPR also seems to be airing more ads and acknowledgements, more teasers and promos, more fundraising appeals and mentions of corporate sponsors, than it used to. I suppose it needs to. But it seems to becoming more like the same mainstream commercial networks that it was originally designed to be an alternative to.

I realize that it is not easy being in public radio these days, when conservatives refuse to recognize their outstanding merits and want to defund PBS and NPR, and when competition for money is so fierce.

But still.

It also doesn’t help that some of the programmers and hosts seem more interested in airing rarities than in disseminating great and inspiring music that gets the pulse going and proves compelling or irresistible. Maybe these programmers know the masterpieces too well, but the rest of us like to hear great and music – not just obscure pieces and neglected composers that interest more than inspire.

So I would urge programmers and hosts to alternate the great and the obscure, and to keep the non-specialist listeners in mind. Some Bax is fine; but lots more Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, to say say nothing of lots more Handel and Vivaldi and Haydn and Mozart and Schubert and Chopin and Schumann and Dvorak and Tchaikovksy and Debussy and Ravel and Stravinsky and Prokofiev and Shostakovich and on and on — is even better.

But then again maybe all this carping comes back to me — to my own taste or personal preferences. So I want to know:

Does anyone out there share my concerns about Wisconsin Public Radio? Or do you think I am totally off-base?

While you consider the question, I think I’ll go to my library to pick out a CD to play instead of listening to the Classics By Request show.

Then I will try turning WPR back on again – and hope I don’t end up once again turning it off until the news comes on.

What do you think of Wisconsin Public Radio, and of its new schedules changes and the music it plays?

Leave something in the COMMENT section.

The Ear wants to hear.

Tags: Antonio Vivaldi, Arnold Bax, Claude Debussy, Dmitri Shostakovich, Franz Joseph Haydn, Franz Schubert, Frédéric Chopin, Friedrich Nietzsche, George Frideric Handel, Heinrich Schütz, Igor Stravinsky, J.S. Bach, James Galway, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Johann Sebastian Bach, Johannes Brahms, Ludwig van Beethoven, Maurice Ravel, NPR, PBS, Robert Schumann, Sergei Prokofiev, Tomaso Albinoni, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Wisconsin, wisconsin public radio, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Classical music: Today is Thanksgiving. Which composer, or piece of music, or performer, do you most give thanks for?

8 Comments

By Jacob Stockinger

Today is Thanksgiving Day in the U.S.

I give thanks for all kinds of music and don’t know how I would live without music. I think of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (below) and his observation in “The Twilight of the Gods”: “Life without music would be a mistake.”

But is there a special reason for or object of my gratitude?

It can and does change from year to year, from age to age, from mood to mood, and from event to event.

But at any given moment there is usually a piece of music for which I give special thanks, music that seems to embody and enhance and grace my existence. Bach and Mozart have done it. So have Chopin and Schumann. Beethoven does it, but to a lesser degree generally.

These days the composer that I, as a devoted amateur pianist, most give thanks for is Franz Schubert (1797-1828), and the pieces by Schubert I most give thanks for are two.

First comes the big last Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major, D. 960, which I can’t play, but the poignant and haunting beginning of which – to say nothing of the rest of the sonata — is especially moving and memorable as performed by Alfred Brendel in his “Farewell Concert” for Decca recording and by Murray Perahia in a Sony Classical set of the last three piano sonatas.

Second comes the miniature “Allegretto” in C Minor, D. 915, also a very late and intimately bittersweet work, which I can play, and which I enjoy as performed by Paul Lewis (on Harmonium Mundi, below) and Maurizio Pollini (on Deutsche Grammophon).

I find Schubert’s warmth and sense of empathy so very touching. His sublime melodies, his sudden major-minor harmony shifts, his sense of accessible counterpoint, his blending of joy and tragedy -– they all are irresistible. Schubert’s music contains worlds, and reassuring worlds at a time when I need to be reassured, and at a time when I also think the world needs to be reassured.

And there is so much music to choose from: the hundreds of fabulous songs and song cycles; the late string quartets, the otherworldly String Quintet, the Octet and the “Trout” Quintet; the Sonatas, Impromptus and Moments Musicaux for solo piano.

In a similar way, famed New York Times senior music critic Anthony Tommasini (below) touched on this same theme in a “Musical Moments” column that he published last week and in which he talked about longtime favorite passages or moments in music by Chopin, Wagner, Puccini and Stravinsky. He even coupled his thoughts to short audio-visual clips he made especially to accompany the column.

You should read and listen to the column, plus pay attention to the more than 600 reader comments:

And here are links to the short videos that he did to go with his column:

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/16/musical-moments-what-moves-us/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/19/musical-moments-part-ii-a-new-video-on-mahler/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/20/musical-moments-part-iii-two-operas/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/21/musical-moments-part-iv-stravinskys-symphony-of-psalms/

And just as Anthony Tommasini asked you for your favorite moments, I am also asking you to leave something in the COMMENT section with the name of the composer or piece of music for which you are most giving thanks this Thanksgiving.

Let me know what they are.

The Ear wants to hear.

Classical music: What is your favorite saying about music? Choose from a website with thousands

8 Comments

By Jacob Stockinger

Do you have a favorite saying or quotation about music?

The Ear does.

“Without music, life would be a mistake.”

That observation comes from the 19th-century German philosophy Friedrich Nietzsche (below).

And there are many, many more with sources ranging from Socrates and Plato to Duke Ellington and J.K. Rowling.

If you don’t already have one in mind, here is a link to a website with hundreds or even thousands to choose from.

http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/music

Take a look.

Make a pick. Or two. Or three.

And leave your choice, along with why you like it, in the COMMENT section.

The Ear wants to hear.

Share this:

Tags: aphorism, Arts, Beethoven, Chamber music, Classical music, comment, Duke Elllington, Friedrich Nietzsche, German, J. K. Rowling, Jacob Stockinger, Jazz, Johannes Brahms, Madison, Music, Neitzsche, opera, Orchestra, philosophy, Piano, Plato, proverb, quotations, saying, Socrates, United States, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Violin, vocal music, Website, Wisconsin, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart