The Well-Tempered Ear

Classical music: The UW Choral Union and UW Symphony Orchestra turn in convincing and moving performances of a neglected masterpiece by Felix Mendelssohn and a great anti-war cantata by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Leave a Comment

By Jacob Stockinger

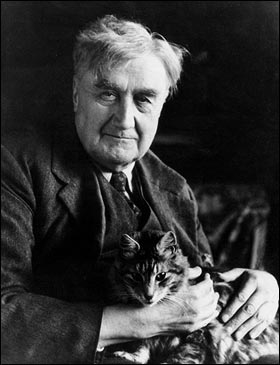

Here is a special posting, a review written by frequent guest critic and writer for this blog, John W. Barker. Barker (below) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who hosts an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT FM 89.9 FM. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the Madison Early Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

By John W. Barker

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Choral Union, conducted by Beverly Taylor, with the UW Symphony Orchestra, gave two performances on Saturday night and Sunday afternoon of a program that deserved even more of an audience than actually turned out.

Only two works were involved, and quite contrasting ones. The first was Felix Mendelssohn’s “Die erste Walpurgisnacht “ (“The First Witches’ Sabbath”), using a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The second was the cantata by Ralph Vaughan Williams, “Dona nobis pacem,” using a deliberately ironic mix of texts.

UW student violist and conductor Mikko Utevsky, who sang in the tenor section, has already described these two works in his preview article recently posted on this blog, so there is no need for me to repeat what he has set out.

Here is a link to his preview:

The work by Felix Mendelssohn (below) is a sadly neglected masterpiece, one on which he worked intermittently down to his last years. It pictures Druid devotees, standing up to fierce persecution by intolerant Christians. The Druids’ weapon is traditional pagan rites, and the making of a ghostly hullabaloo in order to frighten off their enemies. (A precedent not for Halloween but rather for the spooky folk celebrations of St. John’s Eve (celebrated by Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain” and the Brocken scene in Gounod’s opera “Faust.”)

One may debate if the text was worth the effort that Mendelssohn put into it, and whether its brief requirement of a large performing force makes it not an economic concert favorite.

Still, its extended overture is, quite simply, one of the composer’s finest piece of orchestral writing, and the vibrant choral segments are the work, after all, of one of the handful of composers who could compose truly idiomatic choral music.

There were a few rocky orchestral moments at the very beginning of the piece, especially in the strings, and occasional touches of weak co-ordination. But the orchestra pulled together some fine sound, worthy of the standards that James Smith’s training has set for it.

Of the three vocal soloists (below, with conductor Beverly Taylor of the far left) tenor Klaus Georg (middle) had a strong voice, but a not very smooth one. Mezzo-soprano Caitlin Ruby Miller (far right) had such smoothness for her one solo, but not much projecting power. Baritone Erik E. Larsen (second from left) brought a bit more character to his solos.

The real star, though, was the chorus: it can always be counted on for robust sound, and its singers really had a ball working up the Druids’ pagan, anti-Christian frenzies.

The cantata by Ralph Vaughan Williams (below) was composed in 1937, reflecting the composer’s disillusioning experience in World War I, and his just apprehensions about what would become World War II.

An admirer of the poetry of Walt Whitman (below) long before American composers began to pay attention to it, Vaughan Williams took three of Whitman’s poems of American Civil War vintage, adding a few other (mostly Scriptural) passages, which he juxtaposed against the Latin text from the Roman Catholic Mass Ordinary, the “Agnus Dei” — especially its repeated words “Dona nobis pacem” or “Give us peace.”

Such a juxtaposition of compassionate poetry against Latin liturgy was made famous by Benjamin Britten, of course, in his acclaimed “War Requiem.” But, in his more compact venture, Vaughan Williams set a bar of expressiveness so high that not even Britten, with all his cleverness and monumentality, could really match.

Indeed, I would place Vaughan Williams’s cantata as one of the supreme examples of anti-war art–matched not by Britten (if by Wilfred Owen’s poetry) but certainly by the crushing Ancient Greek play by Euripides, “The Trojan Women” and perhaps also Pablo Picasso’s painting of mass horror, “Guernica.”

Each of the movements of the cantata carries potent messages of poignancy and protest, while there is even some final (if uncertain) optimism. The score’s centerpiece is the long setting of Whitman’s “Dirge for Two Veterans,” a movement of absolutely shattering anguish amid discredited military posturing. There are few other things like it in the choral literature.

There are two soloists required for this work. Visiting faculty soprano Elizabeth Hagedorn (below right with Beverly Taylor in the center) was beautifully chilling in the reiterations of the “Dona nobis pacem” motto, while baritone Jordan Wilson (below right) captured the poignancy of Whitman’s “Reconciliation” (at bottom in a YouTube video) a more concise and heart-grabbing predecessor to the culminating Wilfred Owen poem that Britten used in his grander work.

But, again, with stout backing from the orchestra, the chorus was a tower of choral strength, equally forceful in parodistic militarism, in piercing anguish, or in hopeful joy.

Say what you will about the acoustics of Mills Hall in the UW’s Humanities Building, but it is the proper home for a powerful chorus confronting an enthusiastic audience with clarity and presence.

Praise, by the way, for the program booklet, which included all the vocal texts, as well as some excellent program notes. It proved an ideal topping for a rich, but nourishing cake of a concert!

Tags: American Civil War, American Record Guide, anti-war, Benjamin Britten, Brocken, Christian, Dona Nobis Pacem, Druids, Euripides, Felix Mendelssohn, Guernica, Jacob Stockinger, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Orchestra, Pablo Picasso, Ralph VaughanWilliams, Sunday, The Trojan Women, University of Wisconsin–Madison, UW-Madison, Vaughan William, Walt Whitman, war, War Requiem, Wilfred Owen, YouTube

Classical music: Medea remains a fierce and timely heroine for women in today’s society and politics in America.

Leave a Comment

By Jacob Stockinger

Here is a special posting, a review-essay written by frequent guest critic and writer for this blog, John W. Barker. Barker (below) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who hosts an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT 88.9 FM. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the MadisonEarly Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

By John W. Barker

It was just after I filed my review last week for Isthmus on the University Opera’s production of Luigi Cherubini‘s 1797 opera “Medea” that I recognized some startling implications for our time in the popular story of the formidable mythic sorceress.

Here is a link to that review:

http://www.thedailypage.com/daily/article.php?article=38262

Even if I had thought of them before finishing the reviews, there would have been no space for such thoughts.

But perhaps The Ear can find a little niche for them now.

Most people have some inkling of the most famous part of Medea’s story. You know, spurned by her husband Jason, she destroyed his new bride and murdered her own children in revenge. (Sorcery scenes; blood and gore; escape in a fiery chariot — that sort of thing.)

But the full mythological story of Medea (below, depicted in a historical painting) was, in fact, a very complicated and multi-faceted one. It survives to us piecemeal in ancient Greek sources, and is embodied essentially in four phases. First, when the heroic Argonauts, led by Jason, came to her homeland (Colchis, in the Caucasus), Princess Medea fell in love with him, defied her father to help Jason steal the fabled Golden Fleece, and killed her own brother in escaping with Jason.

Upon their arrival in Thessaly to claim his reward, recovery of his throne, Jason was cheated out of it by his uncle, whom Medea promptly killed through her magic wiles.

Fleeing, Jason and Medea took refuge in Corinth for 10 years, where she bore him two sons. Corinth provided the scene of the second phase. Tiring of his forceful wife, Jason renounced her, winning the daughter of Corinth’s king, Creon, as a bride. In revenge, the discarded Medea used her magic to destroy both the king and his daughter, completing her revenge by the calculated murder of both of her sons.

In her vengeance, Medea had come to an agreement with the aged King Aegeus of Athens to take refuge with him. In this third phase of the story, Medea married Aegeus and bore him a son, Medus, but lost out in competition for power with her stepson, Theseus, and had to flee with Medus.

For the fourth and final phase of Medea’s story, she and her son returned to Colchis, where she defeated her hostile relatives and installed Medus as king.

There is, too, an epilogue, in which we are told that the devastated Jason wandered the beaches by the ruins of his famous vessel, the Argonaut. One of its timbers fell off, striking him with a fatal blow.

Now, there is lots of meat in all these episodes. Over the centuries, dramatists of varying stripe have picked over it all. The fourth and final phase has tended to be ignored, but the medium of opera has witnessed treatments of the first three, some going back to the very earliest years of lyric theater.

The episode of Jason and Medea in Colchis had its first operatic treatment (a comic one) by Francesco Cavalli in 1649, and many followed thereafter for three centuries. The third phase, of Medea in Athens, has been given far fewer presentations in opera, the most important being Handel’s “Teseo” (1713).

It has been, however, the second phase, that of Medea in Corinth, which has by far inspired stage versions, making us particularly familiar with that part of Medea’s story.

That emphasis was first laid down by the classical Greek dramatist, Euripides (480-406 B.C), in his play “Medea.” On his model, the Roman writer Seneca (he of Monteverdi’s opera “The Coronation of Poppea”) wrote a simplified drama on the story in Latin, and this was what future centuries knew best of the dread sorceress. French dramatists were particularly influenced by Seneca’s version, and one of them a younger member of the famous Corneille family, wrote the libretto for one of the earliest operatic settings, Marc-Antoine Charpentier‘s “Médée” (1693). (Belwo is Medea from the film by Pasolini.)

That remains one of the best of all such, though that of a century later, Cherubini’s opera–which was the UW Opera presented–does stand out among close to 30 other treatments, their number still growing down to the present. (Below, in a photo of the University Opera production by Brent Nicastro, is Also Perrelli, Shannon Prickett as Medea, and the UW Madrigal Singers in the back.)

What survives to some extent in our various operas is still best set forth at the outset by Euripides. An “issue” dramatist, Euripides liked to provoke his Athenian audiences with challenging and unconventional perspectives.

And in the personality of Medea, Euripides found issues that resound through the centuries, and are more than ever relevant today.

Consider. Yes, Medea is branded as a sorceress — all that nasty magic, bad stuff, we all know, disruptive to nature and to the normal order of things. She had a hair-trigger temper, and her revenge could be simply horrible when she was thwarted. Bizarre character, you know. Someone you might think twice about becoming involved with, and certainly about crossing. (Below is the celebrated opera diva Maria Callas as Medea.)

But what makes Medea so perennially fascinating is the mix of those “negative” characteristics with other elements. She was a wronged woman: betraying her family and abandoning her homeland for love of her man, she is in turn betrayed by Jason when he finds a more advantageous marriage with a young woman.

Complicating her plight are two factors. First, she is a woman in an utterly male-dominated society. Second, in a smugly xenophobic society, she is an outsider, an alien, a “barbarian”, to be scored as something “other”. (Might we say she was the “illegal immigrant” par excellence among the Greeks?) Against both prejudices, she fought bravely, even desperately. Her resources were limited, but what she had she pushed to the extreme. And, until the final phase of her story, she was constantly defeated or on the defensive.

Right now, in our American setting, the rights and opportunities of women are still in question. Breaking through the “glass ceiling” remains a problem for women in the men’s world of business. So-called “women’s issues” are under attack up to the moment: politicians prattle about rape, propose outrageously intrusive gynecology, oppose contraception and sex education, politicize abortion, deny plans for maternity leaves, and assault women’s health care.

Here we have had an election that produced for the first time a total of five women in the U.S. Senate. Not that voting for female candidates must be based solely on gender, but certainly their access to public offices needs strengthening. And how much chance was U.S. Rep Tammy Baldwin (below) first given against for Wisconsin governor Tommy Thompson?

In sum, the situation of women touches on problems whose formulation can be seen as far back as Euripides. Have we learned anything? Perhaps the most provocative anti-war tract ever written was Euripides’ play “The Trojan Women.” And perhaps the best challenge to thinking about the place for women in our world is no less than the same dramatist’s Medea.

And, Euripides might share some credit with the operas, too. I was set to thinking about all this by Cherubini’s “Medea,” in its now “standard” Italian form, as presented by the University Opera’s wonderful student singers.

Overcoming the absolutely silly visual handicaps of set and costumes in William Farlow’s staging, these brave singers succeeded in bringing to vocal and dramatic life so much of what this complex heroine’s powerful story is really all about. (Below, in a photo by Brent Nicastro, is the UW production with, from left) Ariana Douglas, Erik Larson and Aldo Perrelli with the UW Madrigal singers in the background.)

So opera-goers, and everyone else: listen and enjoy, but think.

Tags: American Record Guide, Athens, Colchis, Corinth, Euripides, Golden Fleece, Jason, Luigi Cherubini, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Maria Callas, Medea, Medus